FAQs & Responses

Click on each Objection below for a Response

Response: The 1787 convention did not run away. The runaway claim is based on the assumption that the Confederation Congress called the convention and defined its scope, but that is incorrect. The Constitutional Convention was called by Virginia in December, 1786, and its language gave the states power (under their reserved powers) to re-write the Articles of Confederation. The congressional resolution, issued months after Virginia had issued the call, was, by its own wording, merely an expression of “opinion” and a recommendation. Michael Farris, former President and CEO of Alliance Defending Freedom, has published an article refuting the claim. It is published in Volume 40 of the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy.

Response: The states whose applications trigger the convention retain the right to limit the scope of the convention however they choose. This is inherent in their power of application. In fact, this is the only reason there has never yet been an Article V convention; while over 400 state applications for a convention have been filed, there have not yet been 34 applications for a convention on the same subject matter. Every scholar who has published articles or books on the subject in the 21st century agrees that a convention can be limited.

As the agents of the state legislatures who appoint and commission them, the commissioners only enjoy the scope of authority vested in them by their principals (the state legislatures). Any actions outside the scope of that authority are void as a matter of common law agency principles, as well as any state laws adopted to specifically address the issue.

The inherent power of state legislatures to control the selection and instruction of their commissioners, including the requirement that said commissioners restrict their deliberations to the specified subject matter, is reinforced by the unbroken, universal historical precedent set by the interstate conventions held at least 42 times in American history. Those who make a contrary claim cannot cite a single historical or legal precedent to support it.

Finally, keep in mind that under the explicit terms of Article V, the convention’s only power is to “propose” amendments to “this Constitution” (the one we already have). Only upon ratification by 38 states does any single amendment become part of the Constitution.

Response: It is true that if our Constitution were being interpreted today—and obeyed—according to its original meaning, we would not be facing most of the problems we face today in our federal government. But the problem is today is more complex than that officials are “ignoring” or “disobeying” the Constitution. The real issue is that certain provisions of our Constitution have been wrenched from their original meaning, perverted, and interpreted to mean something very different. Federal officials today follow the Constitutions interpreted by the Supreme Court over the years.

As just one example, consider the individual mandate provision of the Affordable Care Act. Of course, nowhere in the Article I of the Constitution do we read that Congress has the power to force individuals to purchase health insurance. However, our modern Supreme Court “interprets” the General Welfare Clause of Article I broadly as a grant of power for Congress to tax and spend for virtually any purpose that it believes will benefit the people. Now we know from history that this is not what was intended. But it is the prevailing modern interpretation, providing a veneer of legitimacy to Congress’ actions—as well as legal grounds for upholding them.

The federal government doesn’t “ignore” the Constitution—it takes advantage of loopholes created through practice and precedent. The only way to close these loopholes definitively and permanently is through an Article V convention that reinstates limitations on federal power and jurisdiction in clear, modern language.

Response: The Constitution does not spell out the details of processes that were well-known to the Framers (“grand jury” and “habeas corpus” are other examples), and interstate conventions were common practice for them. We know the process from the historical records of past conventions. There have been at least 42 in American history. States always choose and instruct their commissioners, voting is always on a one-state, one-vote basis, and no interstate convention has ever become a “runaway.”

Response: This argument is based on ignorance of existing precedent, holding that Congress may not use any of its Article I powers in the context of Article V. See Idaho v. Freeman, 529 F. Supp. 1107, 1151 (D. Idaho 1981) (“Thus Congress, outside of the authority granted by article V, has no power to act with regard to an amendment, i.e., it does not retain any of its traditional authority vested in it by article I.”) This case was later vacated as moot for procedural reasons, but the central holding remains unchanged. Congress may not use its power under the Necessary and Proper Clause with respect to the operation of an Article V convention.

Response: (excerpted from an article by Professor Rob Natelson):

- This misinterprets the power of the 1787 convention, which met under the states’ reserved powers and not under the Articles of Confederation.

- This contradicts the specific words of Article V, which lays out how amendments to “this Constitution” must be ratified.

- This contradicts 200+ years of Article V court decisions, which rule that every actor in the amendment process must follow the rules laid out in Article V; and

- This defies reality: The convention has no military force nor even any existence after adjournment. How will it enforce its decree? Call out the army?

Response: At the Constitutional Convention in 1787, Col. George Mason promoted the convention procedure specifically as a remedy for abuses of power by the national government. A number of other historical documents confirm that this was the Founders’ intention. (More Info)

Moreover, amendments have been used for this purpose before and have been extremely effective. The Eleventh Amendment was proposed by Congress and ratified by the states specifically to reverse a wrong Supreme Court decision, Chisholm v. Georgia, that had given the federal courts more jurisdiction than they should have had. The problem was corrected through the Article V amendment process.

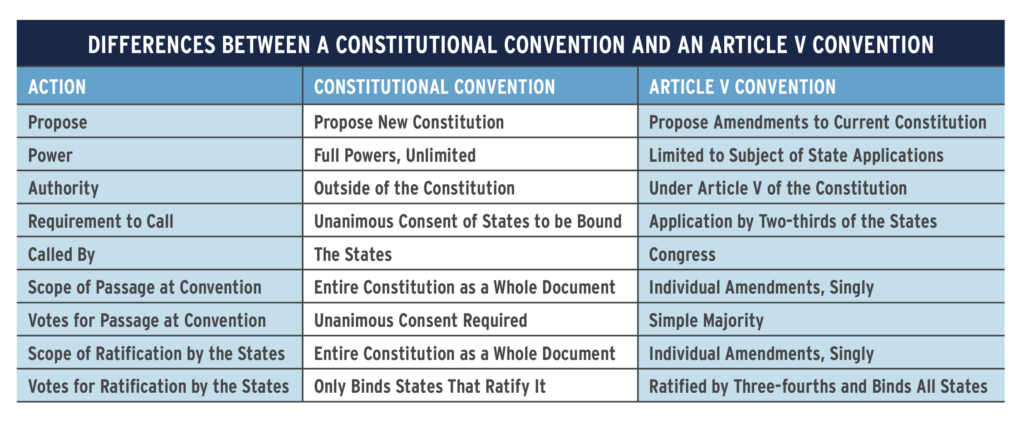

Response: An Article V convention to propose amendments is not the same as a “Constitutional Convention.” At a constitutional convention such as the one in 1787, the states gather pursuant to their reserved sovereignty and the basic right of the people to “alter or abolish” their government as recognized in the Declaration of Independence. At an Article V convention, on the other hand, the states gather pursuant to their power under Article V, and are limited by its provisions. The only power an Article V convention will have is the same power that Congress also has under Article V every day it is in session–the power to propose amendments that would be added to the Constitution (if ratified by 38 states) just like the 27 amendments we already have.

As was the case with the Bill of Rights, each amendment proposed by an Article V convention of the states would have to be ratified individually by 38 states. This is simply not a “re-writing” or “replacing” process. If the states wanted to do that, they would not need to use the Article V process. They would simply gather, as they did in 1787, pursuant to their residual sovereignty. This chart highlights the distinctions between these two types of interstate conventions: